Banks and innovation: opposing views

Much of the transition region continues to be characterised by bank-based financial systems, with only shallow public and private equity markets (see Box 4.1). This raises the question of whether access to bank credit can help firms to innovate in the absence of a meaningful supply of risk capital. Broadly speaking, there are two schools of thought on this issue.7

One group of scholars and practitioners takes a rather pessimistic view and stresses the uncertain nature of innovation – particularly R&D. This makes banks less suitable as financiers for four reasons. First, the assets associated with innovation are often intangible, firm-specific and linked to human capital. They are therefore hard to redeploy elsewhere, which makes them difficult for banks to collateralise. Second, innovative firms typically generate volatile cash flows, at least initially. This does not fit well with the inflexible repayment schedules of most loans. Third, banks may simply lack the skills needed to assess early-stage technologies. Lastly, banks may fear that funding new technologies will erode the value of collateral underlying existing loans (which will mostly represent old technologies). For all of these reasons, banks may be either unwilling or unable to fund innovative firms.

A second school of thought takes a much more optimistic view of the situation. According to this view, one of the core functions of banks is the establishment of long-term relationships with firms, during which loan officers gain a deeper understanding of borrowers. Thus, banks may be well placed to fund innovative firms, as such enduring relationships will allow them to understand the business plans and technology involved.

Moreover, as earlier chapters of this Transition Report stress, firm-level innovation entails more than just R&D. It also involves the adoption of existing products and processes that are new to a particular firm, but not to the wider world. Such imitative innovation is arguably less risky and more in line with the risk appetites of most banks. This is particularly true of banks that have funded specific technologies in the past in partnership with other borrowers. In this case, banks may even act as conduits, facilitating the spread of technology across their borrower base.

Lastly, even without financing innovative projects directly or explicitly, banks can still stimulate firm-level innovation. When banks provide firms with straightforward working capital or short-term loans, this can free up internal resources, which firms can then use to finance innovation. Evidence from a broad range of developed countries suggests that firms generally prefer internal funds to any form of external finance when funding innovation.

The evidence so far

The limited evidence that is currently available suggests that access to bank credit may indeed help firms to innovate. Findings from the United States show that the deregulation of inter-state banking, which increased bank competition during the 1970s and the 1980s, boosted firm-level innovation (as measured by the number of patents that were subsequently filed in the states concerned).8

Meanwhile, evidence from Italy (a more bank-based economy) suggests that increases in the density of local bank branches are associated with growth in firm-level innovation. This effect is stronger for smaller firms in sectors that are more dependent on external finance.9 Firms that have longer-term borrowing relationships with their banks are also more likely to innovate. Lastly, earlier evidence from the transition region indicates that self-reported credit constraints can partly explain cross-firm variation in innovative activity.10

This chapter extends that body of evidence in two main ways. First, the latest round of the BEEPS survey, which includes a separate innovation module (see Chapter 1), allows much deeper analysis of the channels through which access to credit may (or may not) affect firm-level innovation. Second, by combining such firm-level data with information on the exact geographical location of bank branches across the transition region, it is possible to see how local variation in the presence of banks affects firms’ ability

to innovate.

The analysis in this chapter comprises two stages. First, new data on the geography of banking in the transition region are used to improve our understanding of why certain firms are more credit-constrained than others. Second, this chapter then looks at the extent to which such credit constraints affect a wide variety of innovation outcomes. Before that, though, it is useful to look in more detail at how we assess whether a particular firm is credit-constrained or not.

Which firms lack bank credit?

An assessment of the impact that bank credit has on firm-level innovation calls for a clear and unambiguous measure of whether firms are credit-constrained or not. The measure used here is created by combining firms’ answers to various BEEPS questions.

First, we need to distinguish between firms that need credit and those that do not, as only the former can be credit-constrained. Firms that need credit can then be divided into those that have applied for a loan and those that have decided not to apply because they expect to be turned down by the bank. Finally, firms that have applied can be divided into those that have been granted a loan and those that have been rejected by the bank. Thus, credit-constrained firms can be defined as those that need credit but have either decided not to apply for a loan or were rejected when they applied.

Applying this methodology to the BEEPS V dataset, 52 per cent of all firms surveyed reported needing a bank loan. Just over half of those – 54 per cent – turned out to be credit-constrained: they either did not apply for credit (although they needed a loan) or were rejected by the bank when they did. There is, however, substantial variation both across and within countries in terms of the percentage of credit-constrained firms (see Chart 4.1). This ranges from just 26 per cent in Slovenia to 76 per cent in Ukraine. In some Russian regions (such as Rostov and St Petersburg) this percentage is higher still.

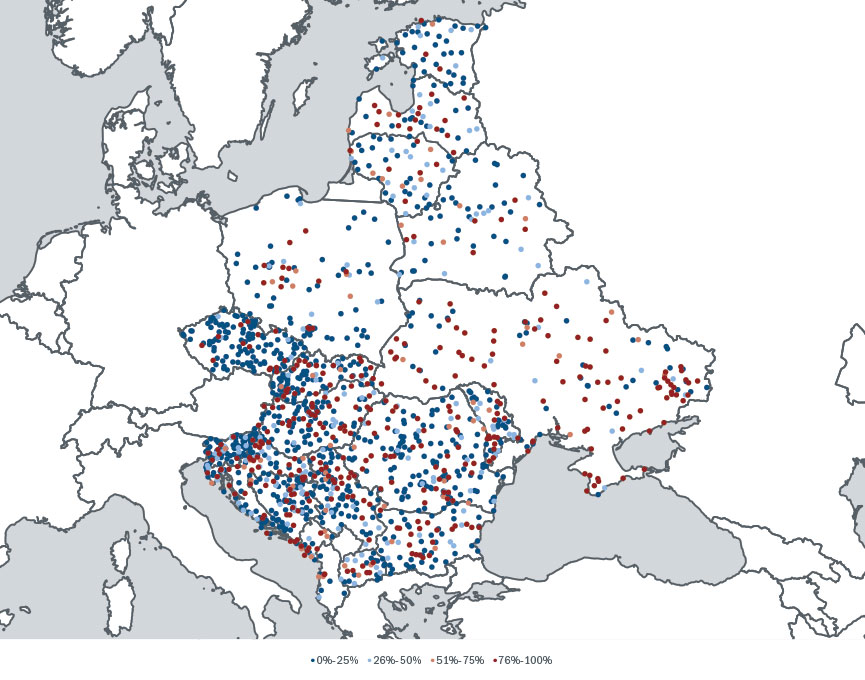

Chart 4.2 provides an even more detailed picture of the regional presence of credit constraints. In this heat map, each dot indicates a town or city where firms were interviewed as part of the BEEPS survey. Red dots indicate areas where a large percentage of firms indicated that they were credit-constrained, whereas blue dots denote areas where only a few firms had problems accessing credit. It is noticeable that there is considerable variation within countries and regions in terms of firms’ ability to successfully attract bank loans. If access to credit affects firms’ ability to innovate, one would expect firms in red areas to have more trouble innovating than firms in blue areas, everything else being equal.

Source: BEEPS V.

Note: Bars indicate the percentage of firms that reported needing a bank loan, but either decided not to apply for one or were rejected when they applied. Blue bars indicate countries, while red bars denote Russian regions.

A heat map showing regional variation in firms’ access to bank credit

Source: BEEPS V.

Note: Each dot represents a town or city where firms were interviewed as part of the BEEPS survey. Red colours indicate a higher percentage of credit-constrained firms in that area, while blue colours indicate a lower percentage.